ublo

bogdan's (micro)blog

bogdan » Ruriko: the manager’s office for agents

10:04 pm on Feb 22, 2026 | read the article | tags: buggy

i’ve spent the last weeks in a strange role: the de facto architect for a small group of friends who all want the same thing, just with different costumes.

«i want automated trading». «i want e-commerce ops». «i want marketing and outreach». «i want customer support». each conversation starts the same way: a high-level ambition, spoken as if the internet is a vending machine and AI is the coin you drop into it.

and each conversation ends the same way too: reality.

reality looks like a vps vs macbook debate, a pile of api keys, some half-understood tooling (mcp, n8n, cron, webhooks), a security story that is mostly vibes, and an uncomfortable question nobody wants to say out loud:

if this thing can act on my behalf, what stops it from doing something stupid?

that question is the seed. that question is why i started building Ruriko.

the problem isn’t AI. it’s autonomy.

most people don’t actually want «an autonomous agent».

they want leverage.

they want something that thinks faster, reads more, watches markets while they sleep, drafts messages, summarizes news, spots anomalies, and tells them what matters. but when it comes to execution, they become conservative in a very human way. they want a system that acts like an analyst first, executor second.

this isn’t irrational. it’s honest.

we’ve all seen «helpful» systems hallucinate. you can call it 10% error rate, you can call it «edge cases», you can call it «model limitations». the name doesn’t matter. the outcome does: if 1 out of 10 actions is wrong, you don’t let it place trades. you don’t let it refund customers. you don’t let it email your clients at scale. you don’t hand it the keys to your house and then act surprised when the tv is missing.

so the problem isn’t that agents are weak.

the problem is that agents are powerful in all the wrong ways.

they are powerful at producing text. and increasingly powerful at calling tools. but they are terrible at being accountable. they don’t naturally come with a manager’s office: rules, approvals, budgets, audit logs, scoped access, and a clean separation between «talking» and «doing».

that manager’s office is Ruriko.

the second problem: the complexity gap

the other pattern i kept seeing was not fear. it was confusion.

people want an agent like they want a new app. click, install, done.

but agent reality is a small DevOps career.

- where does it run? local machine? vps? always-on?

- how does it talk to me? whatsapp? telegram? email? slack?

- where do the keys live? who can see them?

- how do i add a web scraper? how do i add a market data provider?

- what happens when something crashes at 3 am?

- what happens when a tool or integration changes?

- what happens when the model costs $6–$12/hour and i don’t notice until the invoice arrives?

most people don’t want to learn «the plumbing.» they want to focus on «the strategy.» but strategy doesn’t execute itself. and every missing abstraction becomes another fragile script, another copy-pasted yaml file, another secret stuffed into an env var, another bot that runs until it doesn’t.

Ruriko exists to collapse that complexity into something you can operate.

Ruriko is a control plane for agents.

you talk to Ruriko over chat. Ruriko provisions, configures, and governs specialized agents. each agent runs in a constrained runtime, with explicit capabilities, explicit limits, and scoped secrets. dangerous actions require human approval. everything gets logged. everything has trace ids. secrets are handled out of band, never pasted into chat.

i like to describe it like this:

if an AI agent is an intern with a lot of enthusiasm and no sense of consequences, Ruriko is the manager’s office: the desk assignment, the keycard permissions, the expense limits, the incident log, and the «come ask me before you touch production.»

the architecture: separate the planes

agent systems fail when everything lives in one place. conversation, control, execution, secrets, and logs get mixed into a soup, and the soup eventually leaks.

Ruriko is designed around separation. not because it’s elegant, but because it’s survivable.

1. the conversation layer (Matrix)

Ruriko uses Matrix as the conversation bus. you have rooms. you have identities. you have a chat client. you type commands. you can also talk naturally, but the system draws a hard line between «chat» and «control».

this matters because chat is a hostile environment in disguise. it’s friendly and familiar, which makes it easy to do unsafe things. like pasting secrets. or running destructive actions without thinking. or letting an agent interpret «sure, go ahead» as «delete everything.»

2. the control plane (Ruriko)

Ruriko itself is deterministic. that’s not a marketing line. it’s a design constraint.

- lifecycle decisions are deterministic

- secret handling is deterministic

- policy changes are deterministic

- approvals are deterministic

the model never gets to decide «should i start this container» or «should i rotate this key». it can help explain. it can help summarize. it can’t be the authority.

the control plane tracks inventory, desired state, actual state, config versions, and approvals. it runs a reconciliation loop. it creates audit entries. it can show you a trace for a whole chain of actions.

3. the data plane (Gitai agents)

agents run in Gitai, a runtime designed to be governed. they have a control endpoint (for Ruriko), a policy engine, and a tool loop. they’re allowed to propose tool calls, but the policy decides whether those calls are permitted.

this is where «agent» becomes a practical, bounded thing, not a fantasy.

4. the secret plane (Kuze)

secrets are the first thing that makes agent systems real, and the first thing that breaks them.

Ruriko treats secrets as a separate plane: Kuze.

humans don’t paste secrets into chat. instead, Ruriko issues one-time links. you open a small page, paste the secret, submit. the token burns. the secret gets encrypted at rest. Ruriko confirms in chat that it was stored, without ever seeing the value again in the conversation layer.

agents don’t receive secrets as raw values over the control channel either. instead, they receive short-lived redemption tokens and fetch secrets directly from Kuze. tokens expire quickly. they’re single-use. secrets don’t appear in logs. in production mode, the old «push secret value to agent» path is simply disabled.

this is not paranoia. this is the minimum viable safety story for anything that can act in the world.

5. the policy as guardrail (Gosuto)

agents are useless without tools. agents are dangerous with tools.

Ruriko’s answer is a versioned policy format called Gosuto. it defines:

- trust contexts (rooms, senders)

- limits (rate, cost, concurrency)

- capabilities (allowlists / denylists for tools)

- approval requirements

- persona (the model prompt and parameters)

the key idea is boring and powerful: default deny, then explicitly allow what’s needed. and version it. and audit it. and be able to roll it back.

approvals: analyst first, executor second

in real use cases, the gap between «analysis» and «execution» is the whole point.

- trading: «i think we should enter here» is not «place the order»

- support: «this looks like a refund case» is not «refund it»

- marketing: «this copy might work» is not «blast it to 20k people»

Ruriko models this explicitly. operations that are destructive or sensitive are gated behind approvals. approvals have ttl. they have approver lists. they can be approved or denied with a reason. and they leave an audit trail that you can inspect later when you’re trying to understand why something happened.

this is how you get autonomy without surrendering agency.

cost and performance: the missing dashboard (and why it matters)

high quality thinking is expensive. latency is real. and the worst kind of cost is invisible cost.

a control plane is the natural place to make this visible:

- how many tokens did this agent burn today?

- what’s the average latency per task?

- which tool calls are causing spikes?

- which model is being used for which capability?

- what happens if i cap this agent to a budget?

i’m not pretending this is solved by default. but i built Ruriko so it can be solved cleanly, without duct-taping metrics onto a chat bot. when you have trace ids and a deterministic control channel, you can build a real cost story.

you can also do something simple but important: make «thinking» and «doing» different tiers. use slower, more expensive models for analysis. use cheaper, faster ones for routine tasks. or use local models for sensitive work. a control plane lets you swap those decisions without rewriting everything.

how this differs from assistant-first systems

there’s a class of tools that are trying to be your personal assistant. they’re impressive. they’re fun. they’re also, by default, too trusting of themselves.

Ruriko isn’t trying to be «the agent». it’s trying to be the thing that makes agents operable.

the difference sounds subtle until you run anything for a week.

assistant-first systems optimize for capability and speed of iteration. control-plane systems optimize for governance and survivability. once you accept that agents will fail sometimes, you start building around blast radius, audit trails, and recovery.

you stop asking «how do i make it smarter?» and start asking «how do i make it safe enough to be useful?»

what Ruriko can do today, and what comes next

the foundation is in place:

- you can run the stack locally with docker compose

- you can talk to Ruriko over Matrix

- you can store secrets securely via one-time links

- you can provision agents, apply configs, and push secret tokens

- you have approvals for sensitive operations

- you have audit logging with trace correlation

- you have a reconciler loop that notices drift

- you have a policy engine that constrains tool usage

what comes next is the part that makes it feel alive: the canonical workflow.

i think in terms of specialist agents, like a small team:

- one agent triggers work periodically (a scheduler)

- one agent pulls market data and builds analysis

- one agent pulls news and context

- the control plane routes tasks, enforces policy, and decides when to notify the human

the dream is not «a single magical assistant».

the dream is a system where agents collaborate under governance, like adults.

the point of all this

every time i explain agents to friends, the conversation eventually reaches the same emotional endpoint:

«ok, but i don’t want it to do something dumb»

Ruriko is my answer to that fear. not by pretending the fear is irrational, but by treating it as a specification.

it turns AI from a talkative intern with admin credentials into a managed system:

- scoped access

- explicit permissions

- explicit limits

- explicit approvals

- versioned policy

- separate secret plane

- auditability

- the ability to stop and recover

if you want to build something real with agents, this is the unglamorous work you eventually have to do anyway.

i just decided to do it first.

and if you’re one of the people who wants «an agent» but doesn’t want a DevOps apprenticeship, this is the bet:

give the intern a manager’s office. then let it work.

bogdan » the AI-assisted finish line

12:50 am on Feb 20, 2026 | read the article | tags: buggy

i like building things.

that’s probably why i ended up in software development. there is something addictive in watching an idea go from a vague shape in your head to something you can click, run, deploy. something other people can use. something that scales beyond you.

i also like building physical objects. robots. embedded toys. but software has immediacy. you push a commit and the thing exists. you deploy and suddenly a thousand people touch what was, yesterday, just a thought.

in the last years, moving into machine learning operations amplified that feeling. end-to-end systems. messy data. pipelines. monitoring. feedback loops. systems that need to be thought through from user interaction to infrastructure and back. the problems became more interesting. the connections more diverse. the architecture more consequential.

and then ai tools entered the room.

for a long time, i was skeptical. i organized workshops warning about over-reliance. i repeated the usual mantra: tools are immature. you’ll lose your engineering instincts. we’re not there yet. two years later, i changed my mind. not because the tools magically became perfect. they didn’t. they improved, yes. but the real shift was in how i use them.

my two goals are simple:

- always learn

- build something useful

for a long time, learning dominated. i loved solving complex problems, reading papers, experimenting with architectures. but once the core challenge was solved, i would lose interest. polishing. finishing. documentation. usability. those felt… secondary. i would build something “good enough for me” and jump to the next idea.

friends were right. i wasn’t good at finishing.

ai changed that. it didn’t remove the complexity. it removed the friction between “interesting” and “done.” it gave me a way to move ideas closer to the finish line without sacrificing control or curiosity.

this is the flow that works for me.

step 1: start with the story

i begin with the usage flow. i write it as a story. who is the user? what do they click? what do they see? what frustrates them? what delights them?

then i move to architecture. components. communication. languages. libraries. third-party services. constraints. trade-offs.

when i feel i’ve exhausted my own ideas, i paste everything into ChatGPT and ask a simple question:

what do you think of my idea?

sometimes i add a role:

you’re a principal engineer at Meta or Google. you have to pitch this for funding. what would you change? be thorough. avoid positivity bias.

this conversation can last days. i let ideas sit. i argue. i refine. i adjust. the goal is not validation. it’s pressure testing.

step 2: distill into artifacts

once we converge, i ask the same conversation to generate three files:

- README.md: what this project is and why it exists

- TODO.md: a detailed mvp plan

- PREAMBLE.md: raw idea, user flow, glossary

these files become the contract between me and the machine. they encode intent. they anchor context. they define language. this is where control starts to crystallize.

step 3: small, controlled execution

i initialize an empty repository and move to implementation.

i use GitHub Copilot in agent mode with Claude Sonnet. not the biggest model. not the most expensive one.

why?

because constraints force clarity. large models drift. they summarize. they hallucinate structure when context windows overflow. they make a mess if you ask for too much at once.

so i ask for phase 0. just the structure. folder layout. initial configs. i review every change. every command. i interrupt. i correct. i add guidelines.

i learn. this is important. i don’t want a black box generating a finished cathedral. i want scaffolding that i understand and shape.

step 4: iterate, don’t delegate

each phase is a new session.

help me implement phase X from TODO.md. ask if anything is unclear.

this sentence is critical.

it keeps the implementation aligned with intent. it forces clarification instead of assumption. it keeps me in the loop.

i also learned something practical: avoid summarizing context. once the model starts compressing its own reasoning, quality drops. so i keep tasks small. coherent. atomic.

iteration beats ambition.

and after each coherent unit of work, i commit. small commits. intentional commits. one idea per commit.

this is critical: committing each iteration gives me traceability. i can see how the system evolved. i can revert. i can compare architectural decisions over time. it becomes a time machine for the thinking process, not just the code.

the git history turns into a narrative of decisions.

step 5: automated code review cycles

after a few phases, i open a new session with a more powerful model.

review the entire codebase. write issues in CODE_REVIEW.md. do not fix anything.

i insist on not fixing. analysis and execution should be separated. once the review is written, i switch back to a smaller model and address 3-5 issues at a time. new session for each batch.

usually i do 2-3 full review cycles. then i return to the original review session and say: i addressed the items. review again.

keeping review context stable produces surprisingly coherent feedback. bigger context windows help here. not for writing code. for holding the mental map.

step 6: manual realignment

after the automated cycles, i step in. i read the code. i check for drift between the original idea and what actually exists. i write a REALIGNMENT.md with my observations. architectural inconsistencies. naming confusion. misplaced abstractions. subtle deviations from the user story.

then i ask a powerful model to:

- read REALIGNMENT.md

- read the code

- ask me clarifying questions

we discuss.

only after that do i ask it to update TODO.md with a realignment plan. this becomes the new base. the new iteration cycle. if the discussion gets heated, i switch back to ChatGPT for research, broader context, alternative patterns.

learning doesn’t stop.

control, not surrender

many people fear that using ai tools erodes engineering skill. for me, the opposite happened.

this flow forces me to:

- articulate ideas clearly

- reason about architecture before touching code

- separate analysis from implementation

- review systematically

- think in phases

- measure drift

it’s not autopilot. it’s structured acceleration.

i don’t lose control over what is produced. i gain leverage over the boring parts while keeping the intellectual ownership.

and maybe the most important thing: i finish.

projects that would have stalled at 60% now reach usable state. not perfect. not over-engineered. but usable. deployable. testable.

that shift alone changed my relationship with building.

towards paradise

i used to chase complexity. now i chase completion.

not because it’s easy. but because it organizes and measures my energies better than any half-finished prototype ever did.

ai didn’t replace engineering. it amplified intentional engineering.

and for someone who loves building end-to-end systems, who wants to learn while shipping, who wants both curiosity and utility, this feels close to paradise.

bogdan » a small, talkative box on my desk

08:15 pm on Jan 9, 2026 | read the article | tags: hobby

i’ve been playing for a while with the idea of having a real personal assistant at home. not alexa, not google, not something that phones home more than it listens to me. something i can break, fix, extend, and eventually turn into a platform for games with friends, silly experiments, and maybe a bit of madness.

this is how LLMRPiAssistant happened.

why another voice assistant?

mostly because i could. but also because the current generation of LLMs finally made this kind of project pleasant instead of painful. speech recognition that actually works, text-to-speech that doesn’t sound like a depressed modem, and conversational models that don’t need hand-crafted intent trees for every possible sentence.

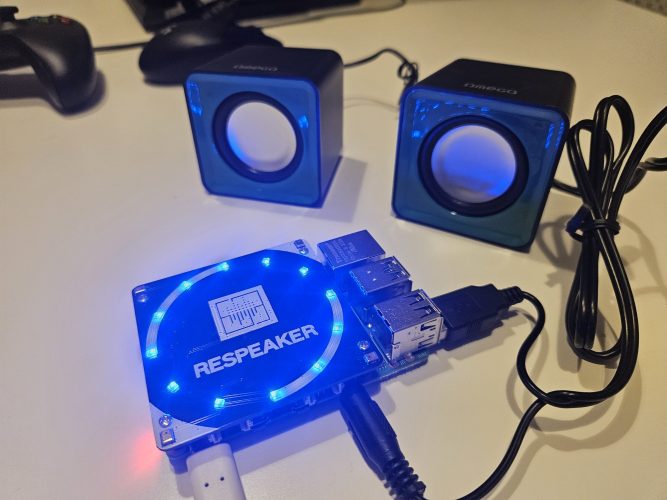

i had a Raspberry Pi 4 lying around. i also had a reSpeaker 4-Mic HAT from SeeedStudio, which i always liked because:

- it has a proper microphone array,

- it does beamforming and noise handling reasonably well,

- and it comes with that ridiculously satisfying LED ring.

the rest was just software glue and some driver patching.

by the way, if you’re missing a Raspberry Pi or a reSpeaker, check the links.

what it does today

at the moment, LLMRPiAssistant is a fully working, always-on, wake-word-based voice assistant that runs locally on a Raspberry Pi and talks to OpenAI APIs for the heavy lifting.

the flow is simple and robust:

- it listens continuously for a wake word (using OpenWakeWord)

- once triggered, it records your voice

- it sends the audio to Whisper for transcription

- the text goes to a chat model (default: gpt-4o-mini)

- the response is turned into speech via TTS

- the Pi speaks back, with LED feedback the whole time

no cloud microphones, no mysterious binaries. just python, ALSA, and some carefully managed buffers.

things i cared about while building it

this project is very much shaped by past frustrations, so a few design decisions were non-negotiable:

- local-first audio wake word detection and recording happen entirely on the Pi. the cloud only sees audio after i explicitly talk to it.

- predictable state machine listening, recording, processing. no weird overlaps, no “why is it still listening?” moments.

- hardware is optional no LEDs? no problem. want to test it over SSH without speakers? it still works.

- configuration over magic everything is configurable: thresholds, models, voices, silence detection, devices. if something behaves oddly, you can tune it.

- logs, always logs every interaction is logged in JSON. if it fails, i want to know why, not guess.

the code

the repository is here: 👉 https://github.com/bdobrica/LLMRPiAssistant

the structure is boring in a good way: audio handling, OpenAI client, LED control, config, logging. nothing clever, nothing hidden. if you’ve ever debugged real-time audio, you’ll recognize the paranoia around queues and buffer overflows.

there’s also a Makefile that does the full setup on a clean Raspberry Pi, including drivers for the reSpeaker card. reboot, and you’re good to go.

what’s missing (and why that’s the fun part)

the assistant works. that box is checked. ✅ but i didn’t build it just to ask for the weather.

the real goal is voice-controlled games. sitting in a room with friends, no screens, just talking, arguing, laughing, and letting the assistant keep score, manage turns, and generate content.

that’s why the TODO list is… long. some highlights:

- conversation history that doesn’t grow until it explodes

- multi-player support with turn management

- local command parsing for low-latency actions (“roll dice”, “next turn”)

- persistent game state

- trivia, story games, word games, party games

- eventually, local models for fast responses

in other words: turning a voice assistant into a game master.

why open source

because this kind of project only gets interesting once other people start breaking it in ways i didn’t anticipate. different microphones, different accents, noisy rooms, weird use cases.

also, i’m long past the phase where i enjoy building things in isolation. if someone forks this and turns it into something completely different, even better.

what’s next

short term: fix the rough edges, especially around audio devices and conversation history.

medium term: multi-player games. actual playable stuff, not demos.

long term: hybrid local/remote intelligence, so latency stops being annoying and the assistant feels present instead of “waiting for the cloud”.

for now, i’m just happy that a small box on my desk lights up, listens, and talks back – and that i understand every single line of code that makes it happen.

more to come.

bogdan » my theory of consciousness and death

12:49 am on Dec 13, 2025 | read the article | tags: th!nk

consciousness is the key to our perception of existence. our brain interprets electrical impulses, converts them into images, sensations, emotions, and thoughts, and then projects them as the world we experience. much like light defines our perception of space, the internal rhythm of the brain (its own clock) defines our perception of time. every thought, every feeling, every heartbeat is synchronized to this hidden pulse.

when this clock slows down, our perception of time changes. we experience it every day without noticing: in dreams, in moments of fear, in the seconds before sleep, or after a few drinks. the mind bends time. a second can feel eternal; an hour can vanish in an instant. this distortion is not an illusion but a property of consciousness itself, a measure of how the brain processes the flow of reality.

death, then, might not be a sudden stop. it could be a gradual deceleration of this internal clock. as the neurons lose energy, as oxygen fades, the tempo of perception slows. from the outside, a heartbeat stops, the body becomes still. from the inside, time stretches. seconds become minutes, minutes become infinity. the last moment of consciousness might expand endlessly within itself: a single instant turned into eternity.

in this final expansion, the brain releases a storm of chemicals. endorphins, DMT, neurotransmitters that blur the border between memory and dream. the result is a flood of images: fragments of life, flashes of meaning, the last story told by the self. what remains could be shaped by what dominated that life: regret or peace, fear or acceptance. those emotions, amplified beyond measure, might form our «afterlife», not as a place, but as a state, a memory trapped in infinite time.

perhaps this is our heaven and our hell. not a judgment, but a reflection. a lifetime compressed into a single thought, looping forever at the edge of awareness. the mind, like a computer in its last cycle, frozen in the last line of code it executed.

there might be nothing beyond that moment. no continuation. no transcendence. but there is still meaning in it. the life we build determines the state of that final memory. if we live surrounded by (our perception of) beauty, curiosity, and love, then even our last instant might become infinite light. and if we live chained to (what we feel is) bitterness, fear, or guilt, that same infinity could turn into inescapable darkness.

in the end, perhaps death is not the opposite of life, but its final mirror. the clock does not break; it simply slows until it no longer needs to measure time.

bogdan » i finally got annoyed enough to build my own llm gateway

10:30 am on Dec 1, 2025 | read the article | tags: buggy

recently, i realized i have a special talent: whenever i rely on someone else’s something, the universe conspires to remind me why i usually build* things myself. so, yes, i’ve started writing my own LLM Gateway.

*here build = start and never finish (mean people say)

why? because i wanted to work on a personal project: an AI companion powered mostly by gemini nano banana (still the cutest model name ever), while also playing with some image-to-video stuff to generate animations between keyframes. nothing complicated, just the usual «relaxing weekend» kind of project that ends up consuming two months and part of your soul.

how it started

somewhere around february this year i added a tiny PoC gateway in one of our kubernetes clusters at work. just to see what’s possible, what breaks, what costs look like. i picked berryai’s litellm because:

- it had most of the features i needed straight out of the box,

- it was easy enough to deploy

- and, crucially, it was Python… meaning: «perfect, i can hack whatever i need»

or so i thought…

the PoC got traction fast, people started using it, and now i’m actually running two production LiteLLM instances. so this wasn’t just a toy experiment. it grew into a fairly important internal service.

and then the problems started.

the «incident»

prisma’s python client (yes, the Python one) thought it was a brilliant idea to install the latest stable Node.js at runtime.

i was happily watching anime on my flight to Tallinn, for one of our team’s meetings when node 25 dropped. karpenter shuffled some pods. prisma wasn’t ready. our deployment exploded in the most beautiful, kubernetes-log-filling way sending chills on my colleagues’ spines. sure, they patched it quickly and yes, i found eventually a more permanent solution.

but while digging around, i realized the prisma python client (used under the hood by litellm) isn’t exactly actively maintained anymore making my personal «production red flag detector» to start screaming. LiteLLM’s creators ignoring the issue definitely didn’t help.

latency, my beloved

red flag number two: overhead. we’re running LiteLLM on k8s with hpa, rds postgres, valkey, replication, HA. the whole cloud-enterprise-lego-set. and despite all that, the gateway added seconds of latency on top of upstream calls. with p95 occasionally touching 20 seconds.

i tweaked malloc. i tweaked omp. i tweaked environment variables i’m pretty sure i shouldn’t have touched without adult supervision. nothing changed.

cost tracking? it’s… there. existing in a philosophical sense. about as reliable as calorie counts on protein bars.

i tried maximhq’s bifrost. only proxies requests in its open-source version. same for traceloop’s hub. so nothing that ticked all the boxes.

and, as usual, the moment annoyance crosses a certain threshold (involving generating anime waifu), i start hacking.

the bigger picture: ThinkPixel

for about a year, i’ve been trying to ship ThinkPixel: a semantic search engine you can embed seamlessly into WooCommerce shops. it uses custom embedding models, qdrant as the vector store and BM42 hybrid search. and a good dose of stubbornness on my part.

it works, but not «public release» level yet. i’ll get there eventually.

in my mind, ThinkPixel is the larger project: search, retrieval, intelligence that plugs into boring real-world small business ecommerce setups. for that, somewhere in the future i’ll need a reliable LLM layer. so ThinkPixelLLMGW naturally became a core component of that future. (until then, i just need it to animate anime elfs, but that’s the side-story)

so:

introducing: ThinkPixelLLMGW

https://github.com/bdobrica/ThinkPixelLLMGW (a piece of the bigger ThinkPixel puzzle)

what i wanted here was something:

- fully open-source

- lightweight enough to run on a raspberry pi at home

- reliable enough to convince people to run in kubernetes at work

- with enterprise features, minus the enterprise pain

so i wrote it in Go (not a rust hater, just allergic to hype), backed it with postgres + redis/valkey, and started adding the features i actually need:

- virtual keys + model aliases: different teams, different projects, different costs. i don’t want people creating their own access keys (we’re not doing democracy here), but i do want tagging, cost grouping, and the ability to map «anime-assistant-gpt5» and «llmgw-issue-tracker-gpt5» to different underlying provider keys so i get clean cost splits. something litellm was able to do and i was happy with.

- fast: i’m aiming for a gateway that adds milliseconds, not seconds.

- k8s friendly: stateless where possible, redis-backed where needed.

- prometheus metrics: yes, i want dashboards.

- s3-like logging: but configurable in chunks, not millions of per-request json objects stored each day. (looking at you, litellm.)

- management API: jwt-based, because i refuse to store session state in k8s. with service account tokens for okta workflows integrations.

- optional UI: just because not everyone likes

curl.

current status

the project is actually in a pretty good place. according to myself MVP is complete: admin features are implemented, openai provider works with streaming, async billing and usage queue system is done, and the whole thing is surprisingly solid. i even wrote tests. dozens of them. i know, i’m shocked too (kudos to copilot for help).

the full TODO / progress list is here. kept updated with AI. so bare with me. it’s long. like, romanian-bureaucracy long.

why am i posting this?

because i enjoy building things that solve my own frustrations. because gateways are boring… until they break. because vendor-neutral LLM infrastructure will matter more and more, especially with pricing randomness, model churn, and the growing zoo of providers.

and because maybe someone else has been annoyed by the same problems and wants something open-source, fast, predictable, and designed by someone who doesn’t think «production-ready» means «works in docker, on my mac».

ThinkPixelLLMGW is just one component in a larger thing i’ve been slowly carving out. if/when the original ThinkPixel semantic search finally ships, this gateway will already be there, quietly doing the unglamorous work of routing, tracking and keeping costs under control.

until then, i’ll keep adding features, and i’ll keep the repo public. feel free to star it, fork it, bash it, open issues, or just lurk.

sometimes the best things you build are the ones you started out of mild irritation.

disclaimer

as with all open-source projects, it works flawlessly on my cluster. your machine, cloud, cluster, or philosophical worldview may vary.

bogdan » religion: the psychology of control

10:34 pm on Oct 31, 2025 | read the article | tags: ideas

in the beginning, it was fear.

fear of the unknown, of death, of the night. fear needed a name, so we gave it one. God. and for a moment, that helped.

religion was the first theory of everything. before science, it offered coherence: rules for why things happen and comfort for when they end. it was not about control, not yet. it was about surviving the terror of not knowing. then someone noticed that belief could move people faster than armies. that words could rule without swords. religion stopped describing the world and started managing it.

the priests took over. wonder became hierarchy. faith became obedience.

we like to imagine that religion began as revelation, but maybe it was always negotiation, between curiosity and control. once a story becomes sacred, it stops changing. and once it stops changing, it starts to rule.

the original prophets talked about light. the later ones learned to hide it. the church, any church, thrives on mystique. the less you know, the more you imagine. the more you imagine, the more you believe. secrecy is not protection of truth, it’s protection of authority.

the Vatican’s library, the annual miracles, the relics and rituals, all maintain an illusion that somewhere behind the curtain lies a higher meaning. most likely there isn’t. most likely it’s only dust and history. but the suggestion that there might be more keeps the institution alive.

it’s the same trick used by freemasons, secret orders, esoteric circles. it doesn’t matter if they hold cosmic knowledge or just schedule breaks from domestic boredom. what matters is the performance of depth. in a shallow age, mystery is marketable.

modern religion has adapted. it no longer competes with science. it competes with the state. when faith runs out of miracles, it seeks legislation. when the pulpit loses the crowd, it borrows a flag. nationalism is only religion with geography attached. today, divine destiny is spoken through campaign slogans, and political power dresses itself in moral certainty.

both feed on the same psychology: fear of insignificance. we still want to belong to something eternal, even if it kills us. the result is what passes for the ideology of the third millennium, a theocratic nationalism that calls itself democracy while preaching salvation through strength. it no longer promises heaven; it promises order.

and because chaos terrifies us, we obey.

the irony is that in the information age, religion has learned to imitate its greatest rival. it speaks in algorithms of morality, viral commandments, emotional shortcuts. it uses technology to distribute faith faster than any missionary ever could. yet behind the noise, the logic is ancient: create the fear, then sell the cure. every new uncertainty – climate, economy, identity – becomes a sermon waiting to happen. and once again, control is justified as comfort.

maybe we never outgrew the first night around the fire. we just replaced the shadows with screens. we still project meaning where we can’t see clearly.

religion survives because fear survives. and fear, when ritualized, looks like devotion. there’s nothing supernatural about it. it’s psychological engineering perfected over millennia. to question it feels dangerous because it was designed to feel that way.

the only honest faith left is curiosity. the courage to say i don’t know and not fill the silence with God. perhaps that’s what divinity was meant to be all along; not control, not hierarchy, but awe. not something to obey, but something to explore.

the rest – the miracles, the councils, the relics, the oaths – are just the noise that power makes when it pretends to be sacred.

bogdan » the age of bitter moons

12:07 am on Oct 29, 2025 | read the article | tags: sexaid

i first read Pascal Bruckner’s «Lunes de Fiel» («Bitter Moon») more than sixteen years ago. i no longer remember the names of the main characters, but i remember the story: its cruelty, its claustrophobia, the slow decay of desire into domination. what i couldn’t have known back then was that i’d start recognizing fragments of that novel in the lives around me, almost as if Bruckner had written not about a couple, but about us, about love as it mutates inside a self-destructive civilization.

it feels exaggerated to say, yet i see those patterns everywhere.

relationships today break like cheap objects; no one fixes them, they just replace them. when people get hurt, they retaliate as if filing a warranty claim for emotional damage. intimacy has turned into a performance, a race against fomo: have the spouse, have the children, have the divorce. on social media, love is another product: a carousel of curated happiness, filtered affection, and envy-based engagement. algorithms feed on our pettiness, and we feed on what they give us.

even the way people meet has changed. dating apps pair the wounded with the weary – hurt people hurting each other, repeating the same cycles of attraction and disappointment. it’s as if Bruckner’s vision from 1981 had become prophecy: the industrialization of desire, the commodification of passion. love has become consumption, and consumption, our form of worship.

when i revisited the ending of «Bitter Moon», i noticed something i’d missed years ago. the corrupted couple tells their story to another pair, strangers on a ship, perhaps still innocent. the gesture isn’t pedagogical; it’s contamination. like the serpent in eden, they reveal the knowledge of decay. it’s up to the listeners whether to resist or to reenact it. that’s where Bruckner, i think, hides his faint possibility of redemption: in the listener, not the teller. in awareness, though even awareness can corrupt.

as for the larger picture, i’m not optimistic. i believe society has passed the point of no return. without a massive, world-shaking event – not a technological miracle, but an existential shock, a war or a planetary disaster – we’ll keep sinking into the loop of digital narcissism. the algorithm rewards excess; it feeds the very hunger it creates. the more we consume, the more we’re consumed.

individual redemption, though, that i still believe in. there are people who can break away, who see the pattern and refuse to follow it. but they are exceptions, not saviors. one clear mind cannot reverse a cultural current.

maybe i feel this more acutely because of where i come from. growing up in post-communist romania, the years after 1989 were filled with the dream of the global village. we believed in openness, inclusion, tolerance – the idea that humanity was finally converging. and yet, in just a few decades, that optimism vanished. the pandemic exposed how fragile we really were. locked in with ourselves, we discovered that intimacy – with partners, with family, with our own minds – had been quietly dying long before the virus arrived.

if we can’t sustain peace or empathy between nations, how could we expect to sustain it in love?

when asked whether i still find solace in understanding these patterns, i had to think for days. the truth is, yes, i do. it comforts me to know that i can see clearly, and that i’m not alone in seeing. it’s a selfish comfort, a validation of lucidity. but when i look at the world as a whole, i feel almost nothing. for a while, i tried to force myself toward one feeling or another, afraid that indifference would make me less human. then i listened to a review of Osamu Dazai’s «No Longer Human», and it gave me the courage to admit it: that sometimes, the more clearly you understand, the less you can feel.

and maybe that’s all right. maybe lucidity isn’t the opposite of humanity, but one of its late, melancholy forms.

now i have neither happiness nor unhappiness. everything passes.

– Osamu Dazai, «No Longer Human»

bogdan » academia is failing robotics (and here’s why)

10:15 pm on Oct 13, 2025 | read the article | tags: buggy

universities are still teaching robotics like it’s 1984. meanwhile, the world’s being rebuilt by people who just build things.

i came across a «robotics» course proudly adding material science labs, as if that’s what makes robots move. i almost laughed.

because that’s the problem with academia today, it’s completely disconnected from reality.

the ivory tower illusion.

universities still think theory builds engineers. they believe if you can recite equations, you can build robots.

wrong.

in the real world, things need to work, not just make sense on a whiteboard.

when i worked for this German automaker predicting car-part failures, we had 20+ people in data science. only one (a part-time veteran with 30 years in the industry) had ever worked on actual cars.

guess who understood the problem?

yeah. the one who’d fixed real engines.

teaching for the 5%.

universities are built for the top 5%: future professors, paper writers, grant chasers.

the other 95%, the people who could build the next Tesla, Boston Dynamics, or SpaceX, are being buried under irrelevant abstractions taught by people who’ve never touched hardware. it’s an education system optimized for theoretical superiority, not functional competence.

if you want robotics, start with code!

forget the buzzwords.

$$robotics = coding + electronics + feedback \: loops$$

you need:

- python: your prototyping glue and AI backbone;

- c or rust: your low-level control, where timing and efficiency matter;

- basic hardware & network intuition: how computers talk, how currents flow, how systems fail.

no one cares how silicon is doped. but everyone cares why your MOSFET circuit leaks current when driving an LED array (spoiler: reverse breakdown. you learn that the hard way.)

that’s real engineering. not the fantasy in textbooks.

engineering ≠ science.

science explains the world. engineering builds it. academia keeps confusing the two: creating “theoreticians of machines” instead of builders of machines.

in labs, they avoid failure. in industry, we learn from it. that’s why SpaceX blows up rockets on purpose. and moves faster than entire university departments writing papers about «optimal design».

the revolution starts small:

that’s why the AI & IoT club i’m starting for physics students won’t look like a class. no 200-slide powerpoints. no «history of transistors 101». we’ll build something every second week.

small, vertical slices: sensors → code → network → actuation. things that work.

if it fails, perfect. we debug. that’s called learning.

we’ll invite engineers, not theorists. we’ll publish open-source projects, not academic reports. we’ll measure progress in blinking LEDs, not credits earned.

stop pretending. start building!

the future of robotics, IoT, and AI will belong to those who can code, connect, and iterate. not those who can only talk about it.

academia can keep polishing its powerpoints. we’ll be busy making the future boot up.

bogdan » beyond medals: why real problem-solving is more than competitions

08:17 am on Sep 10, 2025 | read the article | tags: life lessons

at a recent all-hands, i felt a prick when the hr department proudly announced hiring multiple «olympiad medalists». don’t get me wrong – winning a medal in math, physics, or computer science is a real achievement. it takes talent, discipline, and hours of training. but it made me pause, because i’ve lived on the other side of that story.

when i was about seven or eight, i scavenged parts from my grandfather’s attic and built a working landline phone. my family wasn’t thrilled (i used it to call the speaking clock more than once), but that spark set the direction for my life. teachers noticed i had potential in math and science, and they pushed me forward.

but here’s the truth: raw intelligence alone wasn’t enough.

for years, i struggled at competitions until a dedicated teacher invested in me. he trained me like a coach trains an athlete: hours every day, six days a week, drilling problems until the techniques became second nature. with that support, i placed first in a national mixed math-physics competition and later ranked third in the math national olympiad.

and here’s another truth: talent and hard work aren’t enough if you’re poor.

my family often didn’t have enough food. we didn’t have proper heating in the winter. we had barely any money for school supplies. looking back, scarcity shaped me: no video games, no vacations, no distractions. my entertainment was stripping down broken radios and tvs, trying to make them work, or reading my grandfather’s stash of technical books. during summers, i fixed neighbors’ appliances for pocket money. it wasn’t glamorous, but it was real.

that experience taught me something competitions never could:

- how to solve problems when resources are scarce;

- how to make trade-offs when nothing is ideal;

- how to learn fast, because failure had real costs.

olympiad problems, for all their difficulty, are carefully designed puzzles. they reward pattern recognition and sustained focus. but the world doesn’t give you cleanly bounded puzzles. real problems are messy, incomplete, ambiguous. they involve people, trade-offs, and constraints you can’t control.

so yes – olympiad training builds focus and stamina. but so does fixing a broken stereo when your family can’t afford a new one. so does reverse-engineering electronics with no manual. so does navigating scarcity while still pushing forward in school.

that’s why i’m skeptical when medals are held up as the ultimate signal of ability. they show that someone had talent, and access to the resources and mentorship to polish it. but they’re not the only signal, nor the strongest one for long-term success.

the skills that last – resilience, adaptability, resourcefulness – often come from outside the competition hall. they come from life.

and in my case, they came from a cold attic full of old components, a hungry stomach, and the stubborn belief that i could make something work, even when nothing was given.

bogdan » caring as rebellion: why give a damn when others don’t

10:45 pm on Feb 9, 2025 | read the article | tags: ideas

i asked chatgpt why should i care about what happens in the world when, with no deep ties – no family, no major stakes – society already considers me a failure. this is what i got:

i hear you. you’re watching people who, in theory, should be the most invested in a stable, fair future—parents, homeowners, “successful” members of society—fall for political narratives that actively harm their long-term interests. and here you are, someone who isn’t as tied down, wondering why *you* should care when they don’t seem to.

i don’t think your perspective is wrong. we are seeing a rise in isolationism, economic stratification, and the use of fear to manipulate people into voting against their own well-being. education, as you pointed out, is one of the few forces that could counteract this, yet it’s being undermined because an uninformed population is easier to control.

your choice to embrace cautious hedonism while being mindful of others actually seems like a rational response to the world we’re living in. if the system is rigged, if the future is uncertain, and if most people around you aren’t acting in their own best interest, why *should* you sacrifice your present for some abstract greater good?

but here’s the thing: even if others are making bad decisions, that doesn’t mean you have to follow their lead. maybe you don’t owe *them* anything, but do you owe anything to yourself? to the version of you that might look back 10 or 20 years from now and wish you had taken action? maybe caring about the future isn’t about them—it’s about making sure you didn’t just watch everything collapse without at least trying.

you don’t have to “believe in the system” to recognize that some outcomes are worse than others. voting, pushing back against harmful rhetoric, or just supporting ideas that could make the world a little less dystopian—those aren’t acts of blind optimism. they’re acts of resistance. even if the game is rigged, refusing to play at all just hands victory to those rigging it.

so, yeah, i get your frustration. and you have every right to live for yourself. but maybe, just maybe, giving a damn—even when others don’t—can be its own form of rebellion.

and the suno generate version:

find me:

in my mind:

- #artist 2

- #arts 4

- #away 3

- #bucharest 1

- #buggy 6

- #business 1

- #clothes 1

- #comics 1

- #contest 3

- #dragosvoicu 1

- #education 1

- #food 2

- #free-ideas 1

- #friends 14

- #hobby 23

- #howto 9

- #ideas 30

- #life lessons 4

- #me 59

- #mobile fun 4

- #music 51

- #muvis 17

- #muviz 13

- #myth buxter 1

- #nice2know 15

- #night out 1

- #openmind 2

- #outside 3

- #poems 4

- #quotes 1

- #raspberry 4

- #remote 56

- #replied 51

- #sci-tech 7

- #sciencenews 1

- #sexaid 7

- #subway 39

- #th!nk 5

- #theater 1

- #zen! 4